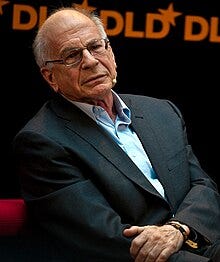

Remembering Daniel Kahneman: 8 Insights on the Psychology of Happiness

Today we remember Nobel Prize winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman and share some of his most important insights...

Daniel Kahneman was a pioneering psychologist who helped us develop a deeper understanding of the human mind: how people think, how people make decisions, and what brings happiness.

His passing earlier this week inspired this article. We’ll begin with three of Daniel Kahneman’s most important happiness research questions then cover five key psychological principles…

Does where you live (climate) matter for happiness?

Would you be happier if you were rich?

What do we mean by happiness?

Question 1… A study from Kahneman and Schkade asked college students in the midwest and in California how happy they were. There was no material difference in the two groups. Interestingly — when midwest students were asked to predict happiness levels of California students they mistakenly predicted that California students would be happier.

This is an example of the focusing illusion. The Focusing Illusion states when our attention is drawn to something, we tend to disproportionately value it in our assessment of happiness. The midwest students, when made to consider differences in climates, over-valued it in their predictions about happiness.

In other words, if you are actively thinking about where you live in comparison to somewhere else then the weather where you live will affect your life satisfaction. But when we look at day to day mood and experiences of happiness there is no meaningful effect.

Putting this into practice: Make choices about where you want to live based on a holistic assessment of job implications, amount of close social relationships, and cost of living as opposed to just the nicest weather.

Question 2… If you had more money it is likely that you would say you are happier (eg more life satisfaction) but you would not actually experience being happier.

This has to do with the focusing illusion mentioned above. When we’re focused on something, we tend to exaggerate its importance in assessing quality of life. Here’s an experimental example from another paper by Kahneman, Krueger, Sckade, Stone & Schwarz.

When college students were asked about their happiness levels and about how many dates they had been on in the last month, there was essentially no correlation. When the questions were reversed, (1) dating life then (2) happiness level, there was a 0.66 correlation. When we call attention to a certain area (in this case dating) we tend to construct our life assessments around that.

The same is true for money. We tend to use it as a cognitive benchmark when trying to think about and assess how happy we are. But when you actually look at day to day and moment to moment emotional states, money has only a marginal impact. While this claim has been challenged by folks like Matt Killingsworth who argue happiness rises with income indefinitely. Kahneman’s other work found that after about $108,000 in today’s income, additional income did not bring much more experienced happiness.

Putting into practice: Be careful not to overestimate dating life, money, or any other one variable in assessing your own happiness level.

Question 3… Kahneman and others have pointed out that there are really two "types" of happiness. You can be happy IN your life: experiences of positive emotion. And you can be happy WITH your life: stepping back and reflecting on it. This is a subtle distinction but one that matters when we think about and try to define happiness.

You will understand the nuances here when you read the “peak-end rule” below…

The important point is we ought to think about being happy in life: moment to moment experiences of positive emotion. This tends to come from rewarding activities, savoring, and time with loved ones. But we also want to balance being happy with life: developing a sense of meaning and accomplishment.

Below you will find a selection of the most important psychology principles from Kahneman…

Peak-End Rule

The Peak-End Rule states that assessment of an experience is based on a combination of the peak emotional tone of the experience and how it ended.

In one study, participants were made to submerge their hands in cold water. One group held their hands in the water for say a minute. In the second group, participants left their hands in the water for an additional 30 seconds, but during that time the temperature of the water was increased slightly. The second group reported a less unpleasant experience than the first even though they suffered for 30 seconds longer. Essentially, they remembered the whole thing as less cold because of how it ended. This shows that the ending of the experience had far greater influence on perception than the duration or actual amount of net suffering.

This has some provocative applications. For instance, this was replicated in patients receiving colonoscopies. One group got a colonoscopy wherein the scope was left in for three extra minutes, but not moved, creating a sensation that was uncomfortable, but not painful. The other group underwent a typical colonoscopy. Kahneman found that, when asked to assess their experiences, patients who did the longer procedure rated their experience as less unpleasant than patients who did the usual way (even though they had three more minutes of discomfort).

When it comes to remembered happiness, what matters is the peak emotional tone and how it ended.

REF — Kahneman, Daniel (2000). "Evaluation by moments, past and future" (PDF). In Kahneman, Daniel; Tversky, Amos (eds.). Choices, Values and Frames. Cambridge University Press. p. 693. ISBN 978-0521627498.

REF — Redelmeier, Donald A; Kahneman, Daniel (1996). "Patients' memories of painful medical treatments: real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures". Pain. 66 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(96)02994-6

Loss Aversion

Loss Aversion states people value losses and gains disproportionately.

We are more sensitive to losses than to gains. We suffer and fear loss to a greater degree than to which we enjoy and desire gain. In fact, economists Kahneman and Tversky estimate that losses are twice as powerful psychologically as gains. For example, imagine your stock portfolio increased in value $10,000. You would likely be quite pleased. Now imagine it decreased $7,500. It’s likely that the anxiety and frustration in scenario two outweighed the excitement in scenario one even though it is less money.

This has roots in evolutionary psychologically. Losing one’s store of food would likely result in immediate death or harm whereas gaining more food wouldn’t necessarily ensure survival. From a survival standpoint it is often logical to prioritize avoiding danger, harm, or loss over seeking to acquire resources.

This of course has application for daily life as we tend to prioritize avoiding losses over acquiring gains and we respond more intensely to perceived losses than to perceived gains.

REF — Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1992). "Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty". Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 5 (4): 297–323.

Anchoring

The Anchoring Effect states an individual’s judgement or perception is influenced by often arbitrary reference points or “anchors”.

In many cases the anchor is irrelevant or illogical. For example, if a $800 couch is placed next to a $4,000 one it more likely to be sold (being perceived as cheaper). Similarly, in negotiation studies the final price often has more to do with the initial price-point (anchor) than the market value of the good.

An interesting example: in one study students were given anchors that were obviously wrong. They were asked whether Ghandi died before / after age 9 or before / after age 140. Clearly neither is correct but when the two groups were asked to suggest when they thought he had died, the before / after age 9 group guessed an average age of 50 whereas the before / after age 140 group guessed an average age of 67.

There are numerous applications here for daily life — broadly, our judgements about prices, numbers, or even probabilities (eg how likely something is / isn’t) are often arbitrarily influenced by cognitive anchors.

REF — Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. (1974). "Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases". Science. 185 (4157): 1124–1131.

Focusing Illusion

The Focusing Illusion states when our attention is drawn to something we tend to disproportionately value it in our assessment of happiness.

For example, if I were to ask you how happy you are from 1 to 10 you may answer 8. Now, if I ask you that same question, but before doing so I ask you one of the following two questions you may give a different answer: (I) How many dates have you been on in the last 6 months? (II) What is your salary?

Based on how satisfied or dissatisfied you are with either your dating life or your income, it will bias the answer to the second question about your happiness. This relates to fact that External factors prime us to feel and behave certain ways.

In short — whenever we focus on something it tends to drive how we construct our self-assessments of life.

REF — Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2006). Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science, 312(5782), 1908–1910. doi.org/10.1126/science.1129688

Adaptation (The Hedonic Treadmill)

The Hedonic Treadmill is the observation that people adapt to positive and negative stimuli.

In other words both good and bad things “wear out” — we “get used to things”. The intensity of emotional response to circumstances tends to decrease with exposure. As time goes one we tend to return to a relatively stable baseline in spite of what happens.

This got its name in an essay by Phillip Brickman and Donald Campbell in which they observed how in the years following a major disability and in the years following winning the lottery, both grouped returned to a relatively similar level of happiness (their baselines from before the respective events).

This of course has serious life applications: as Eric Hoffer said — "You can never get enough of what you don't need to make you happy." It seems that most pleasures in life will wear out: more money, more status, and more sensory pleasures are not the answer.

Note that while Kahneman is not the original theorist behind this, he contributed to it.

REF — Frederick, S., & Loewenstein, G. (1999). Hedonic adaptation. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 302–329). Russell Sage Foundation.

Kahneman’s recommendations for happiness and wellbeing in society

In the conclusion of his seminal 2006 perspective paper on subjective well-being (happiness) in economics. Daniel Kahneman made several recommendations to society in the promotion of happiness and human flourishing…

We should use well-being in determining cost-benefit assessments of policy. We should focus more on connection than materialism. We should be concerned with social standing more than income. We should optimize time allocation and circumstances to support wellbeing.

First, subjective measures of well-being would enable welfare analysis in a more direct way that could be a useful complement to traditional welfare analysis. Second, currently available results suggest that those interested in maximizing society’s welfare should shift their attention from an emphasis on increasing consumption opportunities to an emphasis on increasing social contacts. Third, a focus on subjective well-being could lead to a shift in emphasis from the importance of income in determining a person’s well-being toward the importance of his or her rank in society. Fourth, although life satisfaction is relatively stable and displays considerable adaptation, it can be affected by changes in the allocation of time and, at least in the short run, by changes in circumstances.

REF — Krueger, Alan. (2006). Developments in the Measurement of Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 20. 3-24. 10.1257/089533006776526030.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this relatively research heavy resource. For more on the art and science of happiness for every day life explore StudyHappiness.blog and visit my Youtube @jacksonkerchis.

your happiness nerd,

Jackson K.