Deep Dive into Happiness X Economics

A white paper on the key research at the intersection of economics and happiness....

Hey there — last year I was invited to speak on an economics podcast about research at the intersection of happiness x economics.

The episode was not published because, in a pretty ridiculous turn of events, I shared with the host that while I’m at times critical of it, I generally support capitalism. She said that she could not “give a platform to someone who supports capitalism even if they are critical of it”. After her brilliant display of intellectual depth and maturity I decided to publish it myself HERE.

This inspired me to draft a research primer on all things economics and happiness. If you’re pretty nerdy, you’ll dig it. HERE is a pdf and below is a preview of the topics.

Your happiness nerd,

JK

What is the relationship between how much money you make and your happiness? Part 1

One of the most famous studies on money and happiness comes from Kahneman and Deaton in 2010.

It’s often cited as saying that beyond about $75,000 more money doesn’t make you happier. This is a bit off the mark for a couple reasons. First, you have to adjust for inflation.

The point of diminishing returns in the study occurs around $75,000 which equates to $105,600 in 2023.

Now there is a pattern that generally speaking, as income increases its effects on happiness are less pronounced. The more money you make the less useful each dollar is. $10,000 is a big deal to the average person but not to Jeff Bezos.

This pattern applies primarily to experienced happiness. This is known as satiation point. Like eating – at some point you begin to get full and additional food is not as satisfying. At about $60,000 in household income in 2010 you approach a satiation point for stress. Living paycheck to paycheck and facing financial uncertainty is stressful. Once you know your needs are met, you can relax. The other measures of emotional wellbeing level out around $75,000 in 2010. It is important to note that these are averages and the actual satiation point varies widely based on cost of living, family size, etc.

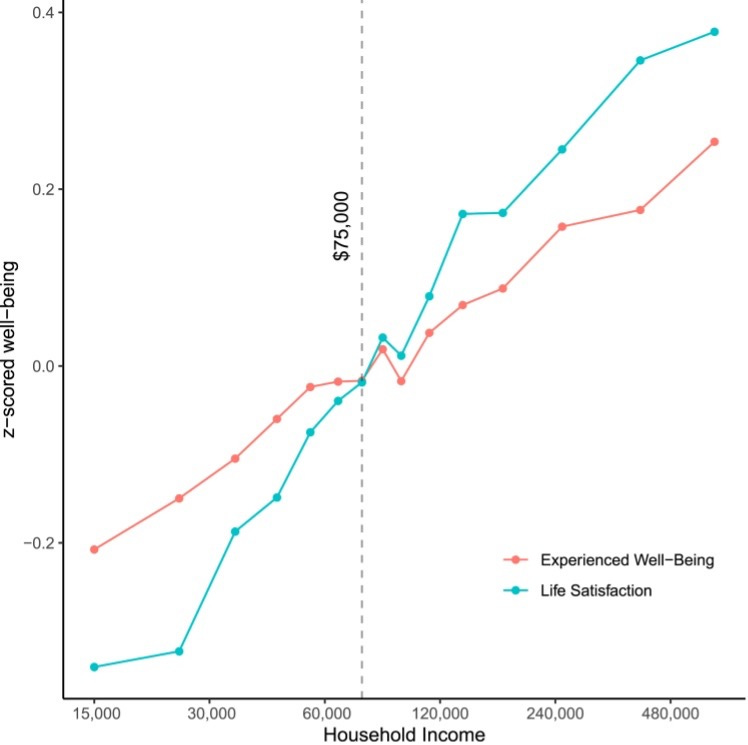

Life evaluation, on the other hand, keeps rising with income. This implies that we often use our income as a shortcut to determine how we are doing in life. This speaks to the role of cultural conditioning in shaping our own sense of happiness.

To summarize this first study - once you have enough money to be comfortable, additional income will likely have minimal effect on your experience of happiness (e.g. positive emotion) but it will improve your evaluation of your life.

What is the relationship between how much money you make and your happiness? Part 2

There has been debate over the above in recent years.

The most well-known example is Matt Killingsworth’s aptly named “Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year”. Killingsworth devised a clever (and more reliable) way to measure happiness. He created an app that prompts people several times per day to rate their happiness. This app captured data from over 33,000 working professionals in the US. He used this data to create a logarithmic description of the relationship between income and happiness. And found that there was no “satiation point” (below).

Killingsworth’s research is sound. However I take objection to his use of a logarithmic scale. Have a look at the x-axis in the above graph. It is not linear - rather the scale is doubling between each value. It’s worth considering the practicality of such a scale. Yale Professor Laurie Santos explains that if you actually plot this, it implies that if you “change your income from $100,000 to $600,000 your happiness goes from like a 64 to a 65”.

The use of the logarithmic scale can obscure the real effect of diminishing returns.

It also does not capture tradeoffs. For practical purposes you can imagine working an additional 20 hours per week for a 150% increase in income is probably not as efficient in increasing happiness as investing a few hours towards additional sleep, exercise, or social interaction.

It seems absolute income is the more practical treatment here. If you are making $97,000 per year and someone offers to double it. By all means say yes. But on the margin there are higher-ROI ways to allocate time beyond the pursuit of more income.

If we have economic growth and abundance why is America still kinda miserable?

First, this not just the old “eye test”.

Data from research published in “The American Paradox” confirms what while we all have a higher standard of living (GDP per capita) - it has not led to a corresponding increase in happiness.

See below.

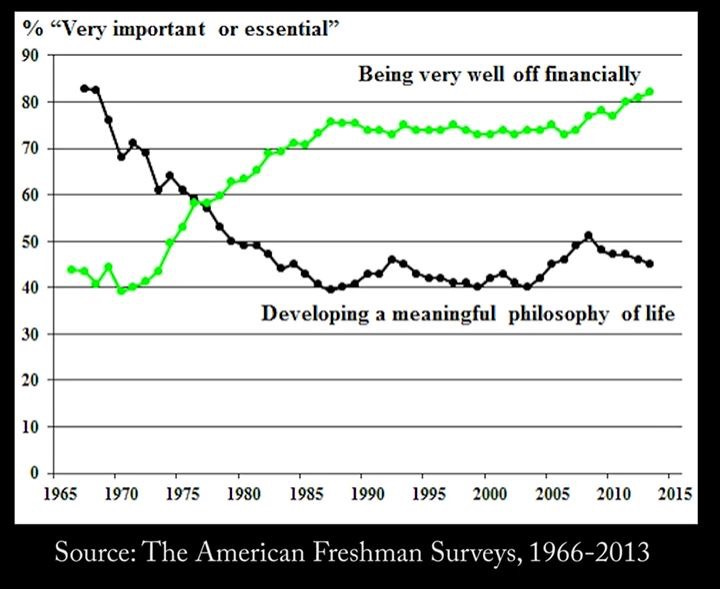

There are several potential explanations for this. In my white paper I explore several but here I’ll cite just one compelling visual. See the below results of the American Freshman Surveys. These surveys ask American college freshman what they most value in life. Notice an alarming trend?

It’s seems the intensity of our consumer culture may be undermining our whole approach to life - making it so that while we’re all earning more, we don’t really know how to enjoy it (especially younger generations)…

See the white paper for more on individual and societal implications of economics x happiness.