Money & Happiness

Happiness Encyclopedia XII from the Happiness PhD Project...

“This answer is money. What’s the question?”

This is, unfortunately, pretty accurate wisdom from a mentor of mine. Putting aside the far-reaching implications of this quote (for business ethics and government incentives especially) – money plays a central role in modern life.

It’s interesting to think that for most of human history, this wasn’t the case. Up until a few thousand years ago the concept of money didn’t exist. And before the Industrial Revolution, while money mattered, most people had a subsistence lifestyle far different from the economic environment we inhabit today.

Any discussion of happiness today would be incomplete if we didn’t talk about money and, naturally, what we do to get it: work. So we’re going to explore the role of work and money in the good life.

There are two main questions:

(1) What is the relationship between money and happiness – does money buy happiness?

(2) What’s the right approach to work – what makes for a good career?

Money can’t buy happiness.

“This sentiment is lovely, popular, and almost certainly wrong.” – Dan Gilbert.

Gilbert is a Harvard psychologist who explains that while money doesn’t buy happiness, it buys an opportunity for happiness. Much of it depends on how much you have and how you spend it.

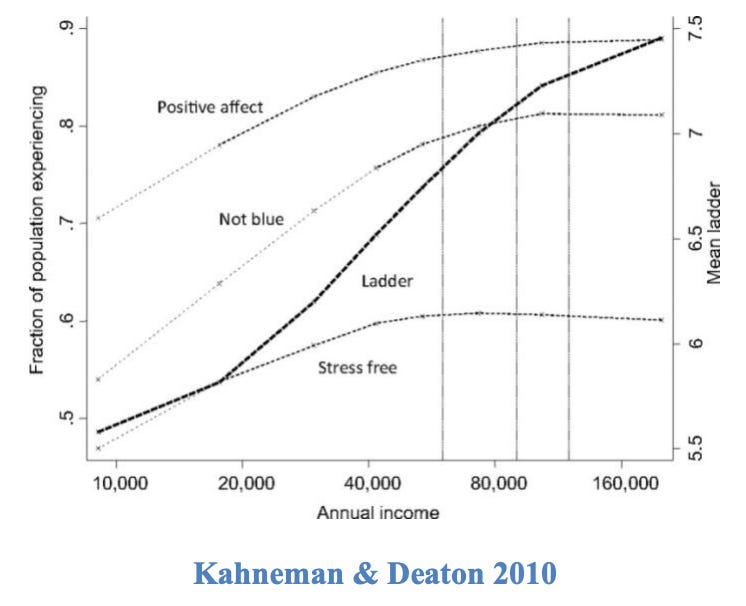

Likely the most famous (and misunderstood) study on happiness and income is Kahneman and Deaton’s 2010 paper: “High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being.” (1) It is often cited to say that beyond $75,000 per year income does not increase happiness. The research is more nuanced than that.

As the title suggests, there are different ways to understand happiness. You can be happy with your life as opposed to happy in your life (as we’ve discussed before). Life satisfaction (with your life) is a more intellectual process of stepping back and evaluating your life as a whole. Emotional well-being, or affect, is the actual experience of negative versus positive emotion in your daily life. It is possible to feel good while dissatisfied with life. And it is possible to be satisfied with life while feeling bad.

The relationship between income and happiness is different based on the type of happiness considered. The authors break up emotional, experienced happiness into positive affect (feeling good), “not blue” (absence of feeling bad), and “stress free.” They use a Cantril Ladder (“Ladder”) to assess life satisfaction. The Cantril Ladder asks you to rate your life as a rung on a ladder where 0 is the worst life possible and 10 is the best.

As income increases, its effects on happiness generally diminish. This makes intuitive sense. The more you have of any resource, the less valuable it becomes on a per-unit level. If you have no car, getting one is very valuable. Getting a second is nice too. Getting a third is probably a pain. Anything beyond that you’d immediately be looking to sell.

So it goes with money. The more money you make, the less useful each dollar is. $10,000 is a big deal to the average person but not to Jeff Bezos.

This pattern applies primarily to experienced happiness. This is known as a satiation point. Like eating – at some point you begin to get full and additional food is not as satisfying. At about $60,000 in household income (~$93,000 in 2026 dollars) you approach a satiation point for stress. Living paycheck to paycheck and facing financial uncertainty is stressful. Once you know your needs are met, you can relax.

The other measures of emotional well-being level out around $75,000 (~$117,000 in 2026 dollars). It is important to note that these are averages and the actual satiation points vary based on cost of living, family size, etc.

Life evaluation, on the other hand, seems to keep rising with income – albeit barely. This implies that we use our income as a shortcut to determine how we are doing in life. And if our income continues to rise, it may slightly improve our subjective life evaluation.

To summarize this first study – once you have enough money to be comfortable, additional income will likely have minimal effect on your experience of happiness (e.g., positive emotion) but it will slightly improve your evaluation of your life.

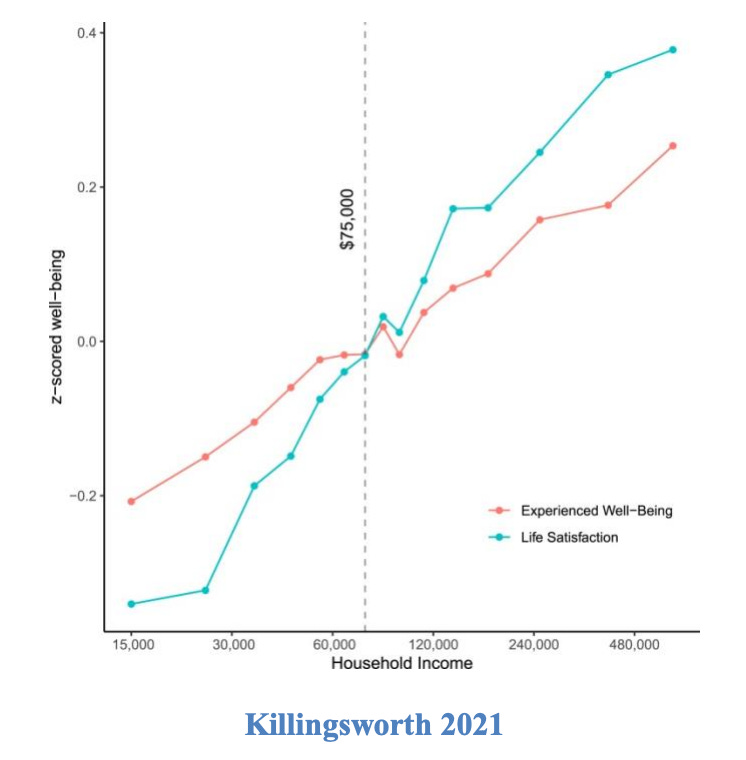

There has been debate over this finding in recent years. The most well-known example is Matt Killingsworth’s aptly named “Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year.” (2)

Killingsworth devised a clever (and more reliable) way to measure happiness. He created an app that prompts people several times per day to rate their happiness. This app captured data from over 33,000 working professionals in the U.S. He used this data to describe a logarithmic relationship between income and happiness and found that there was no “satiation point.”

Killingsworth’s research is rigorous and sound. Nonetheless, it’s worth considering the practicality of a logarithmic scale. Notice how the numbers on the bottom axis are not going up by the same amount every time (e.g., additional $10k). They are doubling every time. In other words, if you keep doubling your income, you will see a small increase in your reported well-being.

Yale Professor Laurie Santos explains that if you actually plot this out, it implies that if you “change your income from $100,000 to $600,000 your happiness goes from like a 64 to a 65.”

The use of the logarithmic scale can obscure the real effect of diminishing marginal utility. It also does not capture relative tradeoffs. For practical purposes, most people are not in a position to continually double their income. The decisions around income are usually something like: Should I take this promotion for a 15% increase and a lot more headaches? Or should I work an extra 10 hours of OT per week for a 25% increase in income?

In these non-logarithmic cases, it seems likely that these linear increases in income are not as efficient in increasing happiness as, say, investing a few hours toward additional sleep, exercise, or social interaction.

It seems absolute income (not logarithmic) is the more practical treatment here. If you are making $80,000 per year and someone offers to double it, by all means say yes. But on the margin, there are higher-return ways to allocate time beyond the pursuit of additional income – especially if you are already earning in the $93,000-and-above range (in 2026 dollars).

These first two studies took a straightforward look at income and happiness. But the income–happiness relationship is more complicated than meets the eye. Relative income, changes in income, and focusing on income are much more important in influencing your happiness than income itself…

Think of the cognitive processes that go into assessing your happiness in the context of income. Research finds it is hard to assess our situation in the abstract. We need standards of comparison: either across time or other people.

A 1996 paper by Clark and Oswald and a 2005 paper by Luttmer show that your income level in relation to your peer group is more important than your absolute income. (3)

For instance, you are likely to be happier making, say, $80,000 surrounded by folks making $40,000 than you would be making $100,000 surrounded by folks making $150,000. This counterintuitive observation speaks to the role of social norms and anchoring.

Additionally, Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, and Stone found that changes in income elicit strong emotional responses, but the long-term effects on happiness are small. (4) Imagine your employer cuts your salary by 2%. You’d be outraged. But this would amount to an immaterial per-year change after taxes (maybe a few hundred dollars). In the long run it would not have much effect.

This same paper calls attention to the “focusing illusion.” This illusion occurs when we are asked to assess our happiness in the context of one specific thing. For example, when college students are asked about their happiness levels and about how many dates they have gone on in the last month, there is no correlation. But when the questions are reversed – how many dates, then how happy – there is a 0.66 correlation.

In other words, when prompted, students subconsciously focused on dating success as a standard to judge their happiness. So studies that directly examine the effect of one variable – e.g., money – on happiness are likely to overstate the effect due to the focusing illusion.

What have we learned so far: Does money matter for happiness? The answer is yes, but it’s a long story.

There are diminishing returns between absolute income and happiness. When your income is low, additional income makes you happier. But once you are well off (around $93,000 to $117,000), the impact is rather minimal. Likely it will only increase your reflective evaluation of life. How much you earn compared to others, changes in what you earn, and whether you focus on what you earn before you think about your happiness matter more than how much you actually earn.

So don’t sweat the changes, don’t compare yourself to your more fortunate peers, don’t focus too much on just money, and aim for financial security (e.g., nearing six figures) rather than getting rich.

Remember though – money buys an opportunity for happiness. How you spend it makes all the difference…

To generate happiness from money, it is best to spend on others, spend on experiences, and spend to save time and reduce suffering.

Spend on others.

Harvard’s Michael Norton is an expert on happiness–money research. He says that money can buy happiness – the key is prosocial spending that benefits not just you, but other people.

In his most well-known study, he and his team asked students if they would be part of an experiment. (5) Their self-reported happiness was measured. Then they were given an envelope with $5 or $20. They were instructed to either spend it on themselves or on someone else.

You might think that the spend-on-others group would see about the same change in happiness as the other group, or perhaps they would be frustrated that they were forced to spend on someone else. In reality, the spend-on-others group reported higher levels of happiness that persisted for several days.

The researchers wondered if this pattern would persist for higher-dollar-value exchanges. So they replicated the study in Ethiopia, where $20 equates to several hundred dollars. They found the same pattern. In line with their other research, this appears to be a human universal.

“Prosocial spending,” or spending to benefit others, makes you happier. (There are even biomarkers that indicate this.)

Spend on experiences.

Van Boven and Gilovich’s 2003 paper, “To Do or to Have? That Is the Question,” shows that spending on experiences translates to greater happiness. (6) Here are a few lines from the abstract that report the survey and experimental findings:

“Do experiences make people happier than material possessions? In two surveys, respondents from various demographic groups indicated that experiential purchases – those made with the primary intention of acquiring a life experience – made them happier than material purchases. In a follow-up laboratory experiment, participants experienced more positive feelings after pondering an experiential purchase than after pondering a material purchase.” (7)

They go on to explore why it is that experiences yield more happiness. They suggest that experiences allow for positive reinterpretations (savoring the memory), are more meaningful parts of one’s identity, and support better social interactions.

This last point is interesting: they found that if you discussed a material purchase, as opposed to an experience purchase, you were rated as less well-adjusted and less enjoyable to be around.

Spend to save time and avoid pain (rather than get pleasure).

If you analyze your spending, there is usually one of two motives behind it. You want to avoid something (suffering, stress, hassle) or get something (pleasure, joy, status).

If you pay for a cleaning service or financial management app, it’s likely the first category – to avoid things you do not want to do. If you buy a snack or a luxury car, it is likely to pursue pleasure.

Research finds that you are usually happier if you spend money to save time on unpleasant activities as opposed to seeking pleasure. In their book Happy Money, Dunn and Norton use the example of outsourcing things you hate doing, such as hiring a cleaning service. Such investments generate more happiness than similar-sized investments in the pursuit of pleasure.

According to Whillans, Dunn, Smeets, Bekkers, and Norton’s 2007 paper:

“Surveys of large, diverse samples from four countries reveal that spending money on time-saving services is linked to greater life satisfaction. To establish causality, we show that working adults report greater happiness after spending money on a time-saving purchase than on a material purchase.”

For greater returns to happiness, it is best to spend on others, spend on experiences, and spend to save time and reduce unpleasantries.

D. Kahneman, & A. Deaton, High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (38) 16489-16493, (2010).

M.A. Killingsworth, Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118 (4) e2016976118, (2021).

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61(3), 359–381. — And — Erzo F. P. Luttmer, Neighbors as Negatives: Relative Earnings and Well-Being, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 120, Issue 3, August 2005, Pages 963–1002.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2006, May). Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion (CEPS Working Paper No. 125). Princeton University, Center for Economic Policy Studies.

Listen to the explanation in Norton’s TED talk: “How to buy happiness”.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2014). Prosocial spending and happiness: Using money to benefit others pays off. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(2), 109–113.

Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To Do or to Have? That Is the Question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1193–1202.